The Rebels Need to Topple the Literary Establishment

Literature needs controversial writers to progress.

When I named this publication Guerrilla Literature, I wasn’t expecting the bill to come so quickly. But it’s already here, in front of me now, smiling. I’ll have to pay for the name with words:

Revolution in literature is now a necessity. Literature stopped breathing years ago. The enemy of innovation in fiction is the Modern Literary Establishment. Guerrilla writers are the antidote. If literature is to have a renaissance, we must arm the rebels. The Establishment won’t.

#

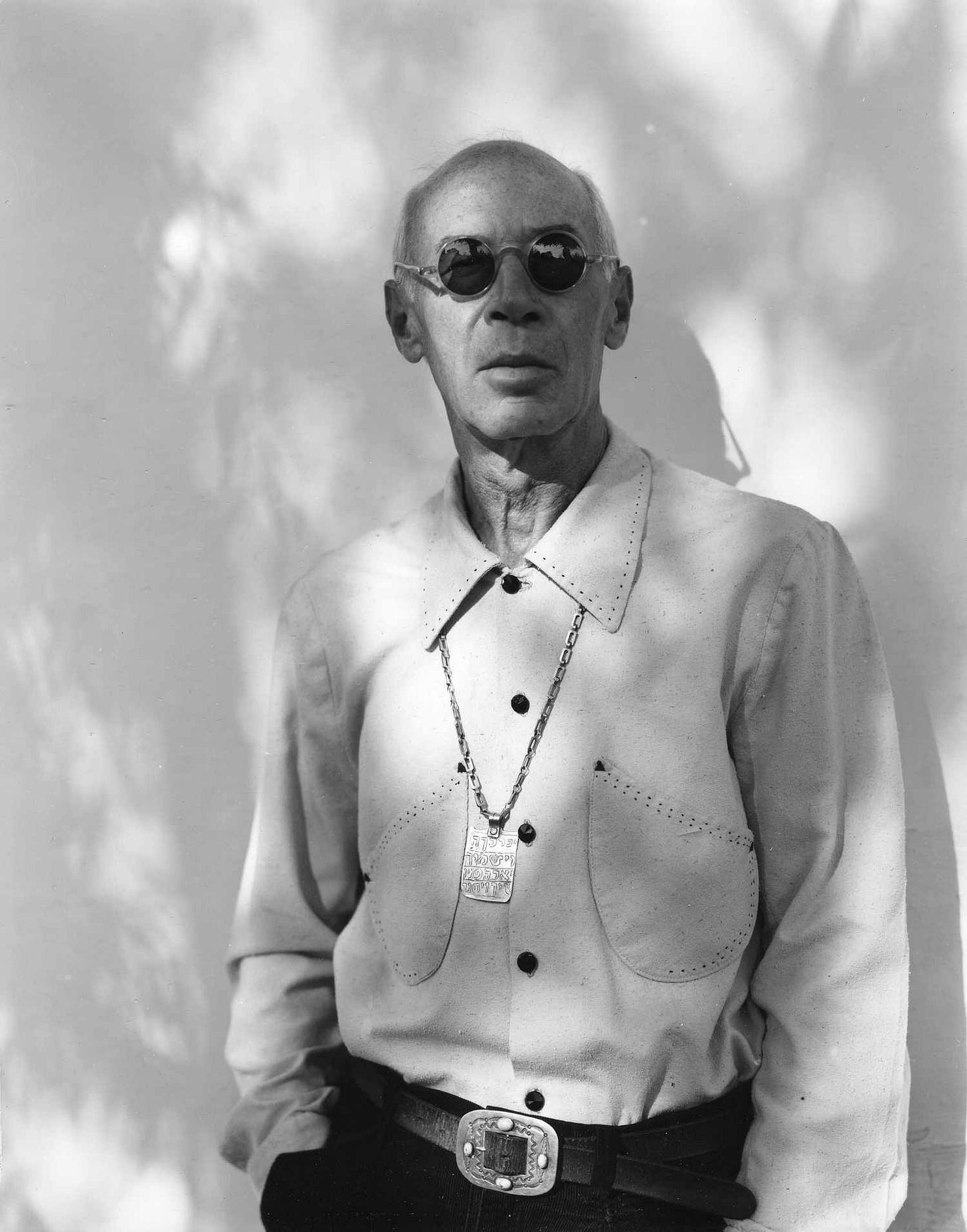

The Literary Establishment is the product of MFA programs, workshops, degrees, journals, magazines, and publishers. Like the old Salon of Paris, it aims to select then propagate what it considers high-quality work; its beneficiaries reap the rewards of access, cash, and “reputation.” But this approval is limited, drastically so, not only in terms of talent but in style and subject matter. Just as the Salon rejected the groundbreaking Impressionists, the Literary Establishment spurns the most controversial, and often original, work in favor of the traditional. Joyce couldn’t find anyone willing to print Dubliners for nine years. Miller, Nabokov, and Burroughs needed to publish in Paris because Olympia was the only company willing to spread their venereal words. Bukowski would have died unknown, a filthy old drunk, if John Martin hadn’t created Black Sparrow Press to circulate his works. Rather than fight for pioneers, the Establishment has repeatedly left them to drown amongst the debris. A fortunate few have been scooped up by a small pirate industry of editors. Then, when the time is right—after the authors have kicked the bucket—it scoops up the successful titles and repackages them as Penguin Modern Classics.

In most cases, the institutions of the Industry are right to ignore the anti-establishment novels they receive. Just because a work is pornographic or reactionary does not mean that it is good. There is nothing impressive in scribbling thousands of dirty words or inventing a series of depraved scenes. But when controversial books also have artistic merit, they are much more powerful than the well-composed works HarperCollins poops out. In guerrilla novels, one finds the crude gutter slang normally reserved for use with close friends, the hurricane of private thoughts and emotions that are too vulgar and shameful to speak. Excellent banned books leopard crawl into the secret crevices of the mind. Not only are they more truthful than the traditional, but more innovative too. The writer willing to mar his reputation or forgo publication is more likely to break all convention than the party man. It was Céline who pushed the novel one hundred years forward because—after first torching the rules of pretentious literary language—he then tore down those of form, structure, and subject matter. Even if the modern reader hasn’t read his works, or those of Joyce or Durrell, he should still be deeply grateful for the rebels: A straight line runs from them through the greats that followed: Vonnegut, Hemingway, Carver, all of the big boys.

If any man ever dared to translate all that is in his heart, to put down what is really his experience, what is truly his truth, I think then the world would go to smash, that it would be blown to smithereens and no god, no accident, no will could ever again assemble the pieces, the atoms, the indestructible elements that have gone to make up the world.

Miller, Tropic of Cancer, p. 201

Unfortunately, by the time the guerrilla writers are rescued from the wash, they are usually battered, sometimes scarily close to being broken. They have been choking on water for too long, not a rack or a line of valuable praise to their names. Though Miller received admiration from his peers after publishing Tropic of Cancer, it wasn’t until he was in his seventies that his novels reached a wide audience. Similarly, Bukowski was off tottering around in oblivion, delivering post office packages, to the deep end of his forties. Denied access to the Salon’s large audience, many avant-garde authors spend their best years toiling away in relative obscurity because breaking into the Establishment is, for them, as difficult as infiltrating a citadel. The exterior wall of the literary journals shoot them down without hesitation, preventing them from reaching the agents just beyond. Without their support, there is no one to haul their works to the center, to knock on the door, to say the password that gets a reading from the mammoth publishers.

For most of the twentieth century, the restrictions at every level of the citadel reliably came from the courts. Lawrence Ferlinghetti was arrested for publishing Howl. Miller’s work was banned by US courts on grounds of obscenity. Durrell’s Black Book was outlawed in Great Britain. Today, however, federal and state bans on book publication are rare.1 Social pressures have taken their place. In the 1990s, Simon & Schuster dropped American Psycho—after paying its author a $300,000 advance—because activists were ready to show up to book readings with tar and feathers. More recently, the senior staff at a major literary magazine resigned after its editor, Elizabeth Ellen, published an interview with Alex Perez that puffed them up to the point of explosion. Within a week the magazine was blacklisted; writers demanded that their work be pulled from Hobart and its beloved offshoots, even though they had absolutely nothing to do with the conversation.

The entire interview is worth reading because it is one of the few cases where people with deep knowledge of the industry state that which everyone knows to be true. Ellen speaks of a magazine rescinding an author’s work after complaints that it was “too bro’y.” She describes how the industry will not publish viewpoints (e.g. being pro-life) that are out of line with liberal politics. And Perez, as a writer, speaks bluntly about his experience on the other side of the equation: how the vast majority of the most powerful players in the industry have nearly identical worldviews; how traditionally masculine perspectives—in the style of Hemingway, Shaw, McCarthy, the sort that were quite common throughout the twentieth century—are derided and disallowed. Ironically, the interview’s extreme backlash immediately proved Perez and Ellen to be correct in their criticism. A crystalline cry echoed through every institution in the Literary Establishment: Do not publish anything—not even an interview, let alone fiction—that is out of line with the Ideology.

The drama was also a rare instance where the Salon’s modern shackles were held up for us to see. Unlike in the twentieth century, the strongest hold is no longer overt but invisible, arising from the institutions’ agreement on what is permissible. An author can submit his work to any literary journal—just like anyone in Russia can run for president—but it is obvious from the outset who will lose. The Salon of Literature is a one-party state. At the university level, the most esteemed presses are run by sensitive students with a uniform outlook, set on rejecting anything that could offend or distress. The larger magazines are no better, except that adults replace students in the hunt for “problematic” sentences that could be construed as sexist or racist. Unsurprisingly, nearly all of the writing the Modern Literary Establishment publishes sounds the same—insipid, anodyne, withered, dead—while it rejects valuable works that might be, in sections, immoral or offensive. This attitude kills fiction because fiction is so damn messy. We need people like Philip Roth who, even though Jewish, could take the good while discarding the bad as he looked past Céline’s vile hatred of Jews:

Even if his anti-Semitism made him an abject, intolerable person. To read him, I have to suspend my Jewish conscience, but I do it, because anti-Semitism isn’t at the heart of his books… Céline is a great liberator.

Originally, I assumed that the internet age would have helped the guerrilla writer circumvent the Salon. For the first time in history, he can cultivate his own following online. No longer does he need to attack the citadel head on. But there are relatively few cases of controversial literature side-stepping the industry and prospering online. The new Bukowskis, Millers, and Nins must be out there somewhere—why haven’t we heard of them?

The first reason has been discussed to death: the climate of political correctness reinforced by social media mobs. An environment where a show as benign as The Office couldn’t be made—where JK Rowling faces a daily barrage of lurid death threats for her personal views—encourages fear and stupidity rather than daring and creativity. For literature to move forward, absurd sensitivity needs to be rebuked rather than stroked, and humanity has to start moving away from the most toxic social media platforms, like Twitter, en masse.

Thankfully, we are heading in the right direction on both of these fronts. The Economist’s analysis found that PC language is starting to fall from the pages of major publications; strange practices, like women paying other women thousands of dollars to tell them that they’re irredeemably racist, have also withered away. Just as importantly, there has been a fantastic push from regulators and folks like Jon Haidt to unplug us from social media, the epicenter of the modern day madness, the diseased universal brain that is poisoning us drop by drop.

Another reason for the dearth of great rebellious writers is because artists are terrible at marketing. They write well but cannot distribute online. These authors will always be dependent on publishers for their reach, but there are few, if any, pirate presses left to appeal to. Olympia went bankrupt in the seventies. Tyrant Books made strides before its founder died. Black Sparrow Press has been swallowed up by big Salon fish. The rebel now has nowhere to turn. Knowing that The Paris Review will reject dangerous words and “unsavory” opinions, his work rots away on his computer.

Fiction needs a new set of subversive publications that welcome what is currently considered heretical. The early successes of one or two presses will encourage other rebels while simultaneously improving the Salon, which will expand its work as the demand for fresh ideas is proven. In the news media, we’ve recently witnessed a similar transformation: Outlets such as The Free Press and Pirate Wires—founded as alternatives to the corrupted “legacy media” outlets—have flourished while having a beneficial effect on their predecessors. The same transformation must come to literature.

This shift is made possible, to a large extent, by the triumph of Substack. Committed to free speech and long-form writing, it is in direct opposition to the social media outlets that have perverted culture in the last decade. Most importantly, it is the first online platform to successfully shift the business model of writing on the internet away from clicks and advertisements toward individuals funding the work they believe is valuable. For the first time in history, men and women, at scale, have the opportunity to champion the next Céline. Those who care about literature should welcome the idea of skipping one burrito a month in favor of personally supporting great artists. If innovation is to return to literature, it will not be because of government grants or billionaire patrons, but because of millions of individuals unified around their care for the individuals producing it.

It is vital that these artists abandon the silos confining them today. In the past, much of great literature came from small bands of kindred spirits working in close proximity: the Lost Generation artists in Paris; the Barranquilla Group in Colombia; the Literary Brat Pack in New York. Nowadays, they are all too disparate, making it difficult for new ideas to reach escape velocity. The lone wolf is at a great disadvantage compared to the outsider surrounded by other rebels like him, groups that can riff on ideas and band together in the face of the Establishment’s fury.

There is no example more pertinent than the Impressionists, a cell that came together with a new unified vision for painting. After their rejection from the Salon of Paris, they formed the Batignolles group, exhibited their world-exploding works in the “Exhibition of Rejects,” and then hosted their own showcase. In the modern era, writers would benefit from seeking each other out through all means—social media, Substack, blogs, in-person events, etc—to form gangs that work as closely together as the Impressionists did.

If we can solve for these deficiencies, there will be a renaissance in the world of literature. For the first time since the eighties, an industry that has been wheezing its way to death will surge back to life. The courageous voices of the twenty-first century will be heard. Fiction will wake from its coma.

Modern day book bans—a subject worthy of its own essay—are still common in libraries. But the severity is much less than the complete outlawing of certain works throughout an entire nation.

Art has always been unfair. It's never been about merit or elevating the avant garde as you point out yourself. So nothing has changed. The battle has always been against entrenched interest because rich people see art as a way to make money. What yall are failing to admit is the market is liberal in the fiction world, the readers are liberal, so why would a publisher put out a book that isn't gonna make them money from their readers. Plus, honestly if a lot of yall were in the traditional media, you would see it's a humiliation routine that doesn't even treat the people it lets inside well. A lot of people with the big five get screwed. As far as writers going rogue, we also need diversity in thought even in that moment. The rogue writers all sound the same, have the same pet peeves, and get sensitive AF when someone who has their same grievances but different takes, engage them in good faith. So the rogue writers gonna have to toughen up and build a wide coalition if yall actually wanna change something.

Great post and says what's needed to be said for at least 25 years now. I remember the change in the late 90's, the cold freeze descending. Fuck MFA writing. I hated it then, hate it now. You could always tell when a book was not backed by a soul with a large sense of life but instead with a large number of college credits. I left the 'creative writing' program at the U of Az specifically because I could see it mediocritize writing in my classes. It was better, as a writer, to go out and get the grit of the world in my teeth.

This is also one of the big reasons men don't read anymore. Literature is no longer of strong spirit. I would love to see this change.