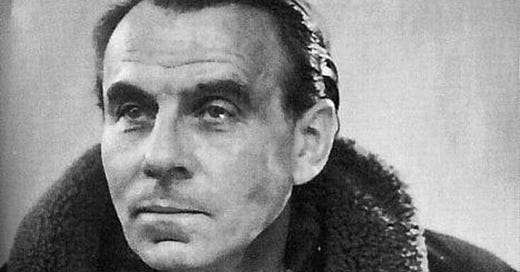

In Spite of His Racism, Céline Is Worth Reading

On the French master's infamous anti-Semitism

My favorite book last year, by far, was Journey to the End of the Night. Back in September I’d lie in the sun, reading forever, addicted to the musicality of the author’s colloquialisms. Published in the era defined by Proust’s ornate language, Journey pushed the novel into modernity. Scorning pretentious literary tropes, Céline turned quotidian, flavorful gutter slang into poetry. With haste he takes the reader through battlefields in World War I, suffocating colonialism in Africa, rattling subway cars in New York, and delirious asylums in the shadows of Paris. No fluff, no facade, no pretension. Just the author’s gritty reality as he experienced it. Yet in spite of the muddy waves that crash over every page, the book left me feeling clean. A new spring had opened up inside of me. Cold clear water started running through my body.

But then things became strange. I knew that I should’ve left Journey alone, but there was no stopping me from looking its author up. If every word is a reflection of the mind that created it, then how can one read that book and not be curious about the forces behind Céline’s? I bought the biography by Frédéric Vitoux to learn about the path that led him to his bleakness, nihilism, despair, and appreciation of beauty—the defining characteristics of Journey. But instead I became entwined, and perplexed, by the side of himself he never showed in the novel: Céline’s vehement, vile anti-Semitism.

#

The whole fiasco took off in the late 1930s. By that time Céline was already a major literary figure. Journey won the critically acclaimed Prix Renaudot and then became the people’s champ, selling over 50,000 copies in two months. The author followed his debut with Death on the Installment Plan, a novel about his youth. Apart from his one thousand references to jerking off—still not to scale, of course—there isn’t much to like about it. The critical response was poor. He might’ve tried to redeem himself with another book, but Europe was already quivering. In response to what Céline correctly predicted was the start of another major war, he penned Trifles for a Massacre in 1937 and School of Corpses one year later. These were not works of literature, but manic pamphlets overflowing with anti-Semitic sewage. The style of writing was so demented that prominent fascist figures in France, such as Robert Brasillach, needed to qualify their endorsement of him. Even Bernhard Payr, the German in charge of French propaganda, kept the writer at a distance. Though he believed Céline’s racism to be correct, Payr couldn’t get behind the author’s “savage, filthy slang” and “hysterical wailing.” Even for the Nazis Céline was too crazy.

If you skim the second book—available for free at schoolforcorpses.wordpress.com, a URL the FBI is probably monitoring—you’ll see what Payr was saying. Not on the racial front, obviously, but with regards to the language. A search for “Jew” yields over six hundred results. Most of the passages are so obscene that I don’t even know where to quote from, so here is one picked more or less at random:

The Jews, racially, are monsters, insane hybrids, mongrels, which must go away. Everything they do, everything they plot is cursed. They are all gangrenous bastards, devastators, rotten people. The Jews have never been persecuted by the Aryans. They persecuted themselves. They’re a result of their own making, their race-mixing of their hybrid flesh. Where does this state of fake asceticism come from? This self-righteous moralism? This arrogance? This extravagant nerve? This euphoric conceit, this bawling insolence which is so disgusting and repugnant?

The reception to these pamphlets was as shocking as the works were horrific. Trifles for a Massacre sold 75,000 copies by the end of the war; School of Corpses reached the substantial count of 25,000; and the response from journalists, both right and left, was relatively muted. In part this is because the language was so scathing that many thought it was a work of irony. But the main reason many were quiet was because racism was extremely commonplace at the time. Just think of the words Hemingway uses to describe Robert Cohn, a Jewish friend of the protagonist in The Sun Also Rises. Or the way Miller rips into Jews at length in Tropic of Cancer. Or take any of the other thousands of examples. It’s enough to remind you of the modern day!

But unlike the students surprised at the professional repercussions for blaming Israel entirely on the night its citizens were beheaded and raped—instead of first showing, you know, a little compassion—Céline was aware of the risk he was running. “I’m not too sure what the future (if there is one!) will bring,” he wrote in a letter after publishing Trifles for a Massacre. “We’ll see. I have no more expectations. For that matter, I have never had any expectations. I shouldn’t like to suffer so much that I’d have to flee. That’s my only wish. It’s a modest one. But I know from experience that I don’t have much luck” (Celine: A Biography 322).

His wish did not come true. Soon after D-Day, Céline ran from France in fear of his life. Unlike his more general paranoias, this time he was correct in his concern. His publisher, Robert Denoe͏̈l, was shot in the head one night on the way to the theater. Charles de Gualle supported executing Suarez, Brasillach, and other writers who collaborated with the Vichy government. Céline was on the blacklist with them, but, unlike many others, he managed to escape. First he went to Germany; then he went Copenhagen where the Danes locked him up for a year and a half at the request of the French government. Finally, in 1951, a frail, broken, and withered Céline made his way back to Paris. He would live there with his wife and pets until his death in 1961.

Like so many others who adored his magnum opus, I struggled to understand how the French master became such a deplorable. One of his biggest fans, Kurt Vonnegut, provided one of the better explanations: the novelist was “partly insane,” though he was never certified by a physician. This truth is self-evident in all of his writings, beginning with the preface of Journey. Before the book even commences, the reader hears all of his paranoia, mania, emotion, and delirium:

Oh, many thanks! Many thanks! I’m raging! Fuming! Panting! With hatred! Hypocrites! Jugheads! You can’t fool me! It’s for Journey that they’re after me! Under the ax I’ll bellow it! between “them” and me it’s to the finish! to the guts!

It’s impossible to determine how much each factor, from childhood experiences to innate brain chemistry, leads one to madness. In Céline’s case, however, I’d wager that the hellish battles of World War I played a major role. For the rest of his life, the author frequently spoke of neurological ailments (i.e. migraines, tinnitus, auditory hallucinations, etc) often associated with serious disruptions in the brain, and he repeatedly stated that the war left him with a serious head injury. In Blueprint for Armageddon, a wonderful audio series on the Great War, Dan Carlin explains how common this was for soldiers of the time. The horrors that befell them made thousands, if not millions, of them lose their minds—permanently.

Beyond the brain injuries themselves, the suffering of war also led to Céline’s anti-Semitism. After going through hell on Earth, he became a vociferous pacifist who believed that one must avoid battle at all costs. Both of his manifestos, and his willingness to align with Hitler’s evil empire, were aimed at preventing another colossal armed conflict. At the time, like almost everyone else in the world, he didn’t know the scale of the malevolence in Germany. But even if he’d had all the details I doubt he would’ve changed his opinion. To him the death of a few million Jews was a better outcome than the much greater civilian and soldier casualties that would come from war—even if that meant that Europe had to live under Hitler’s rule. In School of Corpses, he writes:

Avoiding the war is the most important. The war for us, is the end of the music, it’s the definitive victory of the Jewish mass-grave.

We have to resist the war which the Jews are trying to start more fervently. The Jews are getting excited, with tenacity, Talmudic, unanimous, an infernal procession; we haven’t resisted them aside from a few moos here and there.

We’re going into the Jewish war. We’re as good as dead.

#

Looking into the background of a great artist is like asking for the private tour of a sausage factory. In almost all cases, you’re sure to leave with intestinal sludge dripping from your skin. At least when the artist is alive there’s some value to the information—one can decide whether to support him financially or not—but if he’s dead there’s really nothing to be gained. It really makes no difference to me that J.D. Salinger, at the age of thirty, started a five year courtship of a fourteen year-old girl. Hell, Caetano did much worse and he’s a living hero in Brazil, still selling out venues from Recife to Florianópolis at the age of eighty-two.

Some artists deserve passes and almost endless credit. Others should be boycotted till they die. It all depends on their pulses, their contributions, their crimes.

In the case of Céline, I agree with the protestors who nixed him from a list of national figures to be celebrated in 2011. A country shouldn’t commemorate a man who espoused such incendiary, wretched anti-Semitic views. But the more recent tumult surrounding the publication War, a long lost novel of his, is misguided. The public should continue to read his novels.

Céline wrote musically, tapping his fingers to the beat of words. He used punctuation in an entirely novel way. He created a modern literary language and discovered a new style of delirium. He explored raw subjects at the core of human experience that others were too afraid and ashamed to write about. He was devastatingly funny. He elucidated the vulgar futility of war at a time when most men were enraptured by it. Who better for writers and readers to learn from and enjoy? Without Céline, there’d be no Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac, Kurt Vonnegut—too many others to count. Avoiding his genius, especially now that he is dead, is to squander a great treasure. In the words of a famous Jewish writer:

Céline is my Proust! Even if his anti-Semitism made him an abject, intolerable person. To read him, I have to suspend my Jewish conscience, but I do it, because anti-Semitism isn’t at the heart of his books… Céline is a great liberator.

Well said, Mr Roth.

Why is there no audio to listen to any of your posts? You need at least the AI audio imbed if you aren't going to do the reading yourself.

A lit professor of mine had a theory that Celine was doing satire on fascist propaganda when he wrote those pamphlets. I don't agree at all with the theory but it's out there.